Henry Drummond: Love as a law of life

Blog 1 of 4

Before I ever heard Henry Drummond’s words read aloud, I lived among the realities he was trying to name.

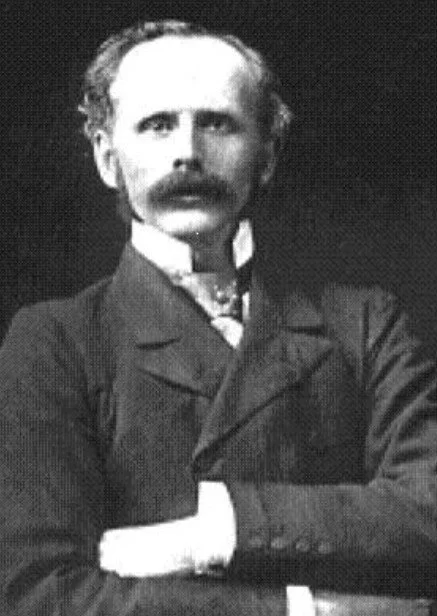

Henry Drummond

"You will find as you look back upon your life that the moments when you have truly lived are the moments when you have done things in the spirit of love".

As an occupational therapist and health professional, my working life is shaped by close attention to how people function, not just physically, but emotionally, socially, and relationally. I am interested in what helps people adapt, endure, and find meaning when life becomes difficult. I am equally attentive to what erodes those capacities.

It was from this perspective that I later discovered Drummond’s work, and recognised in his writing a language for things I already knew to be true.

Who was Henry Drummond?

Drummond lived in the late nineteenth century, a time of rapid scientific discovery and profound questioning about faith and meaning. Trained as both a scientist and a theologian, he resisted the idea that these worlds were in opposition.

Instead, he believed that life, whether physical, psychological, or spiritual, follows patterns and principles. Growth, he argued, is not accidental. It depends on conditions.

This way of thinking makes his work unexpectedly contemporary.

The spirit of man as lived reality

When Drummond wrote about the spirit of man (humanity), he was not referring to something abstract or detached from daily life. He meant the inner life as it is expressed outwardly in behaviour, relationships, and character.

From a modern health perspective, this aligns closely with how we understand human functioning. Body, mind, emotions, and environment are not separate systems; they are interdependent.

Drummond’s insistence was simple and demanding: the spiritual dimension of life, values, meaning, relational capacity, is not optional to health. It is integral.

Love as the central organising principle

Drummond is best known for The Greatest Thing in the World, a meditation on 1 Corinthians 13.

“In 1 Corinthians 13, love is described not as feeling but as way of being: patient, kind, enduring… Love is patient and kind. It does not envy or boast; it is not proud. Other gifts will pass away, but love endures. And now these three remain: faith, hope, and love — and the greatest of these is love.”

Love is presented as observable practice: patience, kindness, humility and endurance.

“Love is not something you have; it is something you do.”

From a behavioural perspective, this matters. Love, as Drummond describes it, is not something we claim but something we enact, particularly under pressure.

Love as health, not idealism

Drummond argued that love functions like a law of life. Just as bodies deteriorate when deprived of nourishment, human beings deteriorate when deprived of love.

This is not moralising. It is observational.

In healthcare, we see this daily. Prolonged isolation, hostility, or disconnection affects mood, cognition, motivation, and physical health. Conversely, safety, belonging, and compassion support regulation and recovery.

Drummond lacked modern neuroscience, but his conclusions align with it: humans thrive where love is present.

Nature as teacher

Another distinctive feature of Drummond’s thinking is his use of nature not as a metaphor, but as teacher. Growth takes time. Environment matters. Neglect has consequences.

One of Drummond’s most distinctive contributions was his insistence that nature teaches spiritual truth. As a scientist by training, he believed the same laws that govern ecosystems also shape human flourishing.

He observed that:

· growth is gradual

· life requires nourishment

· neglect leads to decay

· environment matters

Just as a plant cannot thrive without light, water, and good soil, the human spirit cannot thrive without:

· love

· connection

· purpose

· compassion

Nature, for Drummond, was not separate from spirituality; it was its illustration.

This resonates strongly with occupational therapy’s emphasis on context. People do not struggle in isolation; they struggle within environments that do not meet their needs. And people do not heal in isolation either.

Love, in this framework, is not indulgent. It is structural. It creates the conditions for growth.

Why This Matters Now

Drummond invites us to shift our questions:

not What is wrong with this person?

but What conditions are shaping this behaviour?

For those working in caring professions, this is both affirming and challenging. It suggests that love expressed as patience, presence, and kindness is not separate from skill, but foundational to it.

This piece serves as an orientation to a series of three blogs which I will be sharing this week. The reflections that follow explore how these ideas were encountered, understood, and lived through the lens of my recent experiences. Look out for my next blog in the series.

Author’s Note

I write these reflections as an occupational therapist and health professional, with a long-standing interest in human behaviour, adaptation, and meaning, particularly in moments of vulnerability, transition, and loss. This is not a clinical or theological series, but a reflective one, written at the intersection of professional understanding and lived experience.