When words arrive before understanding

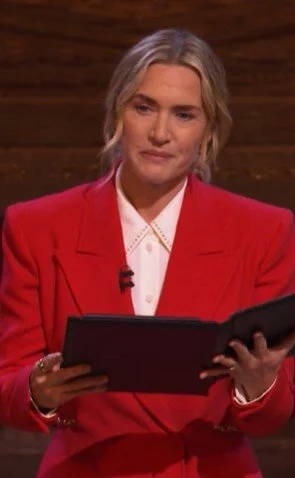

Kate Winslet Together in Candlelight

I first encountered the words of Henry Drummond this Christmas, not in a bookshop or a lecture hall, but through a voice reading them aloud. Listening to Kate Winslet read The Greatest Thing in the World during the Princess of Wales’ Carol Concert, something in the words settled quietly and stayed.

At the time, I didn’t know much about Drummond. I only knew that his reflections on love, written more than a century ago, felt uncannily present. They didn’t demand attention; they invited it.

In the stillness of Christmas, surrounded by candlelight and song, the words landed not in my thoughts, but somewhere lower. In the body. In that place where recognition comes before explanation.

Listening without needing to act

In healthcare, we listen with purpose, to assess, interpret, intervene.

This was different.

This was listening without needing to do anything. And perhaps because of that, the words stayed.

Drummond’s description of love was striking in its simplicity. Not romantic. Not idealised. Defined by behaviour rather than feeling.

As an occupational therapist, I notice how love is lived rather than declared, in routines, in care tasks, in showing up for a loved one. Drummond’s words felt aligned with that understanding: love as practice.

Christmas and togetherness

Christmas heightens awareness of connection. Shared meals. Repeated rituals. Familiar rhythms.

This year, that togetherness felt deep, but not uncomplicated.

Alongside celebration, there was grief and loss. Several family bereavements and funerals unfolded over the Christmas period. Joy and loss sat side by side.

Drummond wrote that love is patient and kind, that it “seeks not its own.” Watching family and friends gather around one another in grief, I understood his words differently. Love revealed itself not as something spoken, but as something carried together.

From both professional and personal experience, I know emotions do not arrive neatly. We carry multiple states at once. This Christmas, that truth was embodied.

And it was here, in warmth and sorrow together, that love became most visible.

Love Observed

What stood out was not what people said, but what they did for each other.

They were present

They were present.

They stayed.

They listened.

They held silence.

In grief, the nervous system seeks safety, not answers. Regulation comes through presence, tone, shared rhythm.

Drummond’s words returned, not as a quotation but confirmation. Love looks like patience. Like kindness without agenda. Like staying and being present.

A question that remained

By the time Christmas passed, curiosity had replaced recognition.

Who was the man behind these words?

What kind of worldview places love at the centre of human life?

Those questions stayed with me as the year turned.

Drummond reminds us that love does not belong to one season. It is the atmosphere in which human life flourishes, in joy and in loss alike.

Author’s Note

I write these reflections as an occupational therapist and health professional, with a long-standing interest in human behaviour, adaptation, and meaning, particularly in moments of vulnerability, transition, and loss. This is not a clinical or theological series, but a reflective one, written at the intersection of professional understanding and lived experience.